New Social Contract: Nepal And Its Young Learning to Co-exist

By Shivanee Thapa Basnyat

Nepal stands at a subtle yet historic juncture.

A republican state, barely two decades old, now faces a generation born after its revolutions, the Gen Z and younger who have no memory of monarchy, insurgency, or transition.

“Our institutions are using the lexicon of the 1950s and 60s,” observes political analyst Bishnu Sapkota.

“Nepal’s major political parties, both at the leadership level and among members- have their ideological training from the Cold War era,” he notes. “They talk about socialism, but never about how to generate resources, create jobs, or mobilize capital to deliver. They can’t even communicate with each other. When the vocabulary itself is worlds apart, how can they truly connect?”

Sapkota believes this ideological nostalgia limits genuine progress.

“Democracy born from revolution is now history,” he argues. “Nepal has moved on. The only reconciliation is to move forward with economic strength, integrity, and a new vision. Even our civilizational past will be respected if we do well in the present.”

His argument suggests that Nepal’s resurgence will depend less on reviving old slogans and more on building credible systems that speak to the aspirations of a generation that values result over rhetoric.

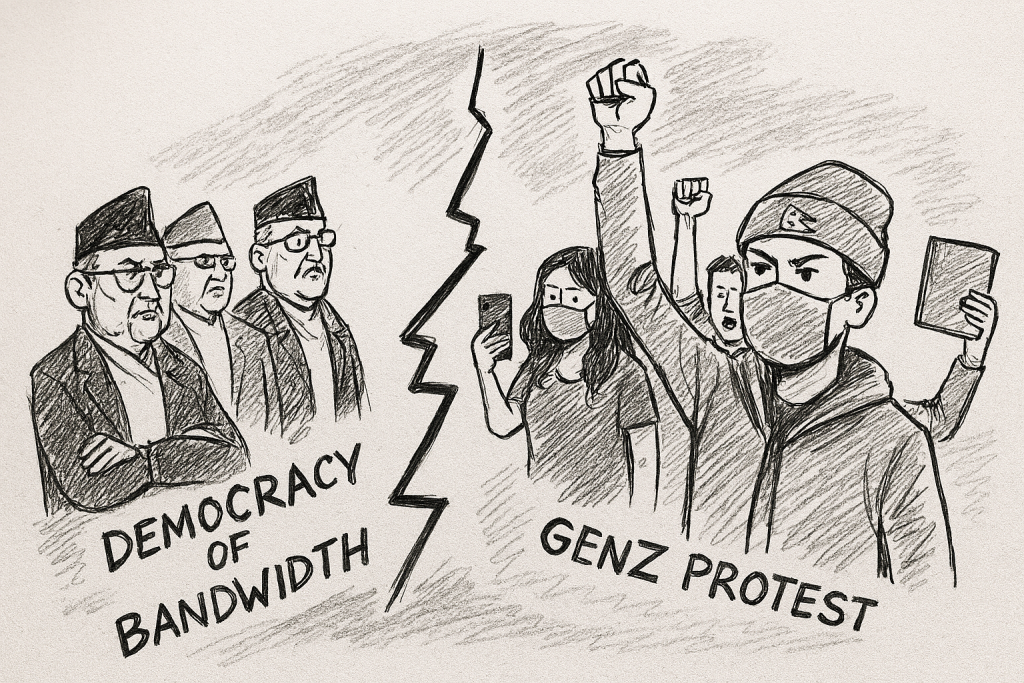

This generational distance, then, is not apathy, it is an asymmetry of memory. The state remembers struggle, the youth demand functionality. Between remembrance and impatience lies Nepal’s new political friction.

Where older parties mobilized around ideology, today’s youth organize around issues like environment, gender, mental health, and digital rights. Their politics is less vertical, more networked, less about slogans, more about participation.

Significant number of Nepal’s voters are now first-time participants. Online, satire, memes, and micro-activism have replaced manifestos as tools of dissent.

The public square has migrated to the comment thread, yet the impulse remains democratic, to be heard, to belong.

Institutions designed for paperwork governance now face the immediacy of a digital public sphere.

Parliamentarians tweet before they legislate, ministries crowd-source ideas, mayors are measured by Facebook likes as much as by policies.

Media expert Ujjwal Acharya believes that the traditional hierarchy of communication has fundamentally shifted.

“Authority has lost its monopoly on narrative,” he notes. “Public discourse now happens across platforms that no one can fully control or regulate. The best way forward for the political establishment is to listen, to be transparent and trustworthy in response.”

According to Acharya, the digital era demands authenticity rather than control.

“If intent is genuine, institutions can adapt to the scrutiny of digital citizens,” he explains. “They must realize they can no longer afford to be elusive. They can no longer depend on traditional mindsets, they need to embrace with open arms, the changes brought about by technology.”

Acharya points out that this transformation places a special responsibility on the media itself.

“Nepal’s media, in particular, have the strongest presence in this ecosystem and must take a stabilizing role, practicing accuracy, balance, and professionalism. Too often, some outlets become part of the turbulence by chasing virality over value.”

This new feedback loop is forcing bureaucratic adaptation. Some officials resist, branding it “populism”; others embrace transparency as survival. The state, in effect, is being social-mediated into responsiveness.

The democratization of speech has escaped its digital origins. From tweets (now X) to coffee tables, discourse now travels fluidly between online and offline worlds.

Kathmandu’s cafés and campuses echo that evolution, places where activism feels conversational, and conversation itself becomes activism.

“We don’t want to overthrow systems, we want to update them,” says a young artist from Patan.

This redefinition of citizenship from obedience to co-creation is the hallmark of Nepal’s new democratic experiment.

What earlier generations called it protest, this one calls it participation. Their dissent is aesthetic as much as political, visible in music, fashion, and digital storytelling.

Beneath the noise of activism lies a quieter sociology, a search for trust.

Gen Z inherits institutions born in compromise; opaque, hierarchical, and slow.

They crave authenticity, leaders who mean what they post, not only what they pledge.

Elders often misread this as arrogance, when it is, in truth, fatigue with pretense.

This is the first Nepali generation that audits credibility in real time.

“They don’t wait five years for elections, they judge daily,” explains Dr. Bishnu Upreti, Public Policy Researcher.

For him, the impatience of a connected generation is not recklessness but realism, a demand for accountability that moves at the speed of information.

Dr. Upreti adds that traditional institutions are struggling not just with capacity but with concept, not only in Nepal but across the world.

“Institutional change is slow and resistant by nature,” he notes, “while young people’s expectations are fast and high. That gap defines today’s tension.”

In his view, this generation is not replacing ideology; it is bypassing it.

“Do new public spaces like TikTok, podcasts, or online petitions represent inclusion or echo chambers?”

“Hierarchy, seniority, domination, these are not the leadership traits they entertain,” says Dr. Upreti.

Political parties and parliaments are not obsolete, but the rise of networks and narratives has become powerful enough to reshape political discourse itself.

The digital sphere amplifies this shift. “Do new public spaces like TikTok, podcasts, or online petitions represent inclusion or echo chambers?” Dr. Upreti says “Possibly both.”

The risk, he cautions, is a widening digital divide, between urban and rural, rich and poor, and between those fluent in technology and those only beginning to engage.

Yet even within these divides lies new possibility. As another scholar observes, “In a country of uneven infrastructure, technology has become an equalizer of imagination.”

Rural creators now narrate their own realities, diasporic youth remix patriotism with pop culture. “This digital awakening,” he adds, “widens voices even as it exposes divides between the connected and the excluded, the globally fluent and the digitally learning.”

Nepal’s democracy thus enters its most complex stage, a democracy of bandwidth.

The question, then, is not whether Nepal’s elders understand Gen Z, but whether both generations can learn interdependence. The youth need institutional memory, the establishment needs youthful legitimacy.

“Nepal’s future stability depends on our ability to turn generational tension into institutional learning,” notes one civic educator.

That learning, he adds, runs both ways, elders mentoring in context, youth mentoring in technology. This symbiosis may shape Nepal’s modernization more profoundly than any infrastructure project.

As Nepal urbanizes and digitizes, the unwritten contract between state and citizen is being revised in real time. The vocabulary is shifting, from development to dignity, from order to openness.

Coexistence, in the end, is not about silence or surrender; it is about synchronization. And Kathmandu, with all its contradictions, may yet find that rhythm.

(The author is Senior News Editor at NTV World and can be reached at thapashivanee@gmail.com)

Comments