How Much of Our Thought Is Truly Ours?

Shivanee Thapa Basnyat

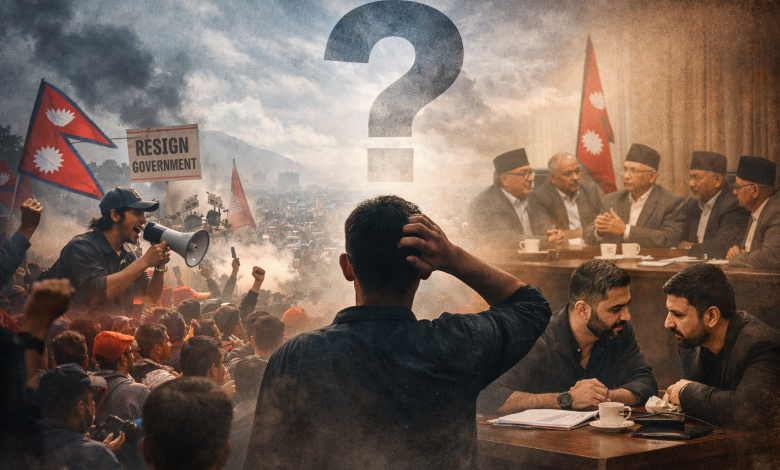

Nepal is passing through a moment that feels crowded but curiously unsettling.

Nepal, today, is loud but uncertain, protests erupt, meetings prolong, slogans spread faster than clarity and beneath all this is a quiet hesitation about what comes next.

A collective pause. A wait-and-watch mood.

This contradiction is perhaps most visible in the much-discussed Gen-Z movement.

Still at an early stage, its rise has been swift and its moral appeal strong. Calls for accountability, clean governance, and transparency have struck a chord across society.

Yet, its political articulation remains fluid; learning as it moves, sometimes unsure of its own direction.

The movement entered into an agreement with the interim government.

Soon after, one faction announced nationwide peaceful protests, demanding the government’s resignation, citing inaction and non-delivery. The contradiction is not necessarily malicious.

It reflects a movement still searching for coherence, structure, and an institutional anchor.

All this is unfolding at a time when the state itself is navigating a political vacuum.

The interim government’s constitutional mandate, to hold elections, appears simple on paper.

In practice, it demands what is hardest in moments of volatility: consensus-building. Bringing all sides on board is not just a procedural exercise; it requires patience, trust, and political maturity.

Traditional political parties, meanwhile, are looking inward even as public expectations rise.

CPN-UML has concluded its 11th National Congress, re-electing KP Oli, an outcome that has drawn attention and shaped perception, reinforcing continuity at a time when many are calling for change.

The Nepali Congress is preparing for its own congress, once again grappling with familiar questions of leadership and direction.

On the left, forces have regrouped under the banner of the Nepali Communist Party, under the coordination of Pushpa Kamal Dahal, signaling another attempt to consolidate a fragmented ideological space.

At the same time, newer political actors, often framed as alternatives to the established order, are signaling coordination and intent.

A marathon meeting involving Kathmandu Mayor Balendra Shah and Rastriya Swatantra Party chair Rabi Lamichhane sent a message that was hard to miss.

Around the same period, senior leaders of the UML and Nepali Congress held one-on-one discussions, while the President convened an extended meeting of top political leaders.

These overlapping developments are unlikely to be mere coincidences.

Figures such as Balendra Shah, Rabi Lamichhane, and Kulman Ghising have emerged as symbols of decisiveness and action. Their assertiveness has energized public discourse. At the same time, it has sharpened divisions, often reducing complex governance questions into simple binaries of heroes and villains. Whether this moment leads to renewal or deepens political polarization remains an open question.

And it brings us to a more uncomfortable reflection.

How much of our thinking is truly our own?

In an age of infodemics where opinions circulate faster than facts and outrage often outpace reflection, our political consciousness is shaped in real time.

We absorb narratives, share fragments, and take positions before pausing to question them.

Movements gain legitimacy through visibility. Leaders are judged by presence rather than by their ability to build institutions.

This does not make public anger illegitimate.

Nepal’s frustrations are real and long-standing.

Corruption, weak service delivery, and governance failures have eroded trust over decades.

The moral energy behind protests, particularly those led by younger citizens, is understandable, even necessary.

But moral conviction alone does not substitute for political preparedness.

When demands lack clarity or sequencing, the risk extends beyond any single government.

It reaches the foundations of the polity itself.

Instability without strategy does not automatically produce reform.

It can just as easily prolong uncertainty, delay elections, and weaken already fragile institutions.

The Gen-Z movement, like Nepal’s newer political forces, now stands at the crossroads. Will it mature into a structured, inclusive platform capable of engaging power responsibly? Or will it remain reactive, fragmented, and driven by momentary consensus?

The state, too, must confront difficult questions. Can it listen without absorbing dissent into symbolism? Can it engage without weakening legitimate demands? Can it reform without merely managing discontent?

Nepal’s future will not be shaped by a single movement, a single leader, or a single election.

It will depend on how thoughtfully this in-between moment is navigated, where old certainties are being questioned, but new ones have yet to take shape.

Perhaps the most important task before us is this: to slow down. To examine our assumptions. And to ask, quietly but honestly, whether our views are formed through reflection, or merely echoed from the loudest voices around us.

Because the strength of a democracy is not measured only by how loudly it speaks, but by how deeply it thinks.

Comments